Aggressive Fish

Imagine this: you own a fish farm featuring a particularly aggressive species of fish. One day, a group of divers trespasses onto your property and ends up injured by these fish. Naturally, they sue you, citing strict liability for their injuries. Who would win this case? The answer, surprisingly, depends heavily on where this fish farm is located.

The United States and France offer contrasting legal approaches to such a scenario, revealing different philosophies underlying their tort law systems. The American system, while emphasizing individual responsibility, takes a more limited approach to strict liability, particularly when trespassing enters the equation. French law, however, prioritizes victim protection and casts a wider net with strict liability, applying it even in cases involving trespass.

In the US, strict liability primarily comes into play when dealing with dangerous activities, such as running a nuclear power plant. The inherent risk involved puts the onus on the operator to assume all associated resulting harm.

Applying this principle to animals creates a gray area. The concept of a "dangerous animal" is subjective and inconsistently applied, leading to potentially unfair outcomes. Would a playful Labrador be considered dangerous if it nipped someone? What about a large but docile Great Dane? These ambiguities are a significant point of contention in American tort law.

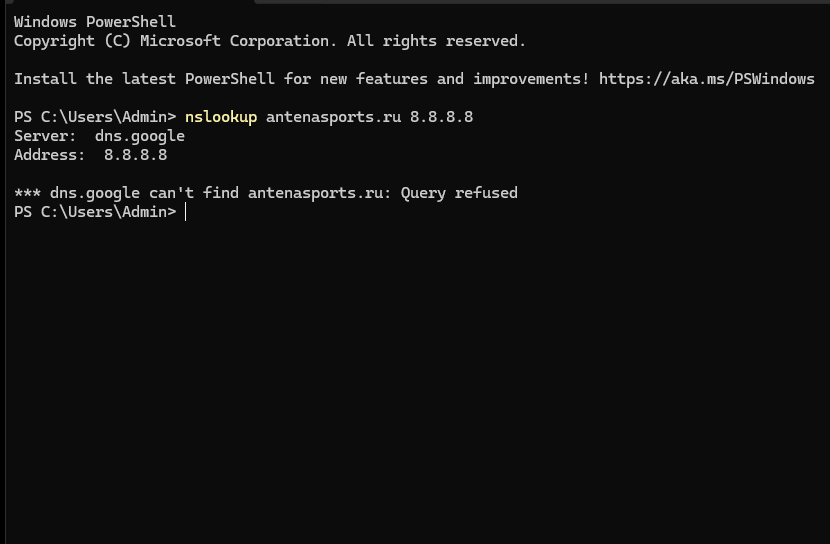

The US legal system's stance on trespassing further muddies the waters. American case law generally bars lawsuits under strict liability if the injured party was trespassing. So, in our fish farm scenario, the trespassing divers would likely lose their case regardless of the fish's aggressive nature. This approach leans heavily towards individual responsibility, seemingly favoring property owners over those who infringe upon their property rights, even if those infringements are relatively minor.

Across the Atlantic, French law paints a different picture. Article 1243 of the French Civil Code lays out a clear and comprehensive approach to animal liability, stating that the owner is responsible for any damage caused by their animal, regardless of the animal's dangerousness or the victim's actions. This seemingly straightforward rule, however, has its own set of nuances.

While strict liability is the default in French animal liability cases, the legal system allows for two levels of exoneration: total and partial. Total exoneration, is reserved for force majeure events - those that are unforeseeable, unavoidable, and external to the liable party - and represents a high bar to clear. Trespassing, generally foreseeable and often avoidable, doesn't meet the criteria of force majeure.

Partial exoneration, however, offers more wiggle room. If the victim's fault contributed to the harm, the judge can reduce the liable party's obligation to repair the resulting damage. In our fish farm case, the divers' deliberate trespassing could lead to partial exoneration for the owner, meaning they might only be responsible for a portion of the damages. In practice, partial exoneration for the fish farmer would almost certainly be granted, perhaps even up to 95 percent.

This system grants French judges significant discretion, allowing them to consider the specific circumstances of each case and apportion liability accordingly. This flexibility, combined with France's widespread and comprehensive liability insurance system, creates a framework that seeks to protect victims while acknowledging the complexities of real-world situations.

The juxtaposition of these legal systems reveals contrasting priorities. The American system, while acknowledging the concept of strict liability, seems to prioritize individual responsibility and property rights, even when dealing with minor offenses like trespassing. The French system, in contrast, leans towards a more pragmatic approach, emphasizing victim protection and employing a robust insurance system to handle the financial repercussions of strict liability -- a system which will be the topic of a future episode.