Eloka Ferry (1921)

The Eloka Ferry case of 1921, decided by the French Tribunal of Conflicts, offers a glimpse into the complexities of colonial governance, the intersection of industry and public service, and the evolution of legal distinctions within a system marked by racism and exploitation. The case, which revolved around the sinking of a government-operated ferry in the French colony of Ivory Coast, ultimately established a key distinction in French law between public services of an industrial or commercial character (SPIC) and public administrative services (SPA).

To understand the Eloka Ferry case, it is essential to grasp the context of French colonialism in the early 20th century. Unlike other colonial powers, France aimed to integrate its colonies as extensions of mainland France, imposing French laws, administration, and culture on its colonial subjects. This included establishing legal and administrative systems that mirrored those found in metropolitan France, with the aim of creating local elites assimilated into French culture.

The Ivory Coast, like many other African colonies, was subjected to brutal exploitation under French rule. The French focused on extracting natural resources such as rubber, coffee, cocoa, and palm oil, often relying on forced labor and violence to achieve their economic goals. The Ébillé Lagoon, a 130-kilometer stretch of water separating the coastline from the interior, posed a significant challenge to colonial infrastructure development, making the government-operated ferry service a crucial link in the extractive chain.

On September 5, 1920, the Eloka Ferry sank, carrying 18 passengers and four vehicles. Tragically, one colonial subject lost their life in the incident. The West African Commercial Company, a company involved in resource extraction, owned one of the vehicles on board and sought compensation from the colonial government for damages. The company requested an expert assessment of the damage from the Civil Tribunal of Grand-Bassam, the colonial capital, assuming the matter fell under private law and the judicial jurisdiction.

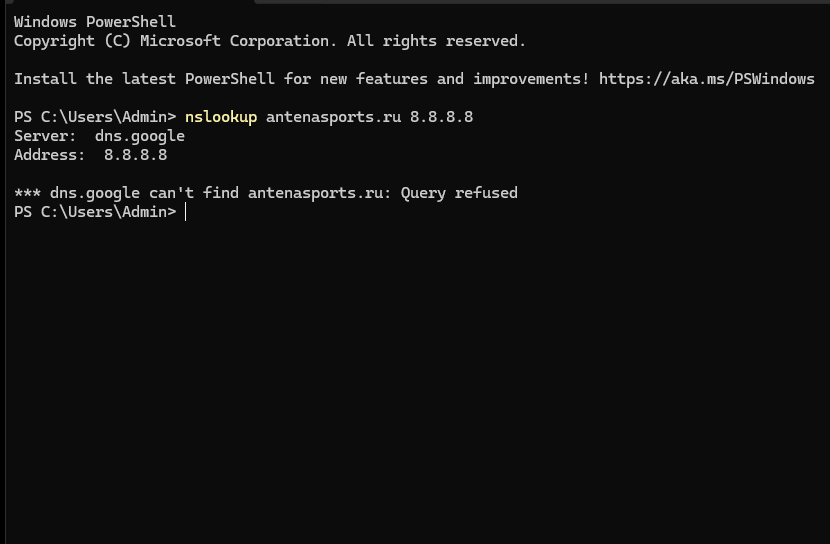

The lieutenant Governor of the Ivory Coast, however, challenged this assumption, arguing that the case belonged to the administrative jurisdiction, which governs disputes involving the state and private persons. This meant the involvement of the Tribunal of Conflicts, a court located in the Palais Royal in Paris, tasked with resolving jurisdictional disputes between the judicial and administrative branches of the French legal system.

The Tribunal's role is not to decide the merits of a case, but rather to determine which court system is competent to hear it. This distinction stems from the fundamental difference between private law, which focuses on protecting individual interests, and public or administrative law, which prioritizes the public interest and grants the administration certain freedoms to act in its pursuit.

Two competing theories emerged prior to the Eloka Ferry case. The government argued for administrative competence based on the theory of public service, claiming that the ferry service, even if operated a private company might, was a public service and thus the case ought to belong to the administrative courts. This theory suggests that the government, when providing public services, deserves the protection of the administrative jurisdiction, in the name of the public interest.

Conversely, the West African Commercial Company, seeking full compensation, argued for judicial competence based on the theory of public power. This theory posits that the administration's special protection should only apply when it exercises powers exclusive to the state, such as policing or passport issuance. When acting as a private company, the government should not enjoy any advantage over private competitors, and disputes should fall under the judicial jurisdiction.

The Tribunal of Conflicts ultimately sided with the West African Commercial Company, ruling that the government-operated ferry service fell under the purview of the judicial jurisdiction. The Tribunal argued that the colony, by charging for the ferry service and operating under conditions similar to an ordinary business, acted as an industrialist rather than a sovereign power.

This decision, based on the theory of public power, established the distinction between SPIC and SPA, shaping the understanding of administrative competence in French law for over a century. The case's legacy extends beyond liability and compensation, influencing the legal status of public service employees and defining the boundaries of administrative jurisdiction.

While the Eloka Ferry case established a significant legal precedent, it is crucial to acknowledge the troubling colonial backdrop against which it unfolded. The dispute between a colonial government and a private company engaged in resource extraction highlights the inherently exploitative nature of the French colonial project. The case, while significant from a legal standpoint, arose from circumstances steeped in racism and economic dominance.

Moreover, it must be noted the Tribunal of Conflicts, situated in the heart of Paris, decided the fate of a distant colony based on telegraphed information, highlighting a certain disconnect between the legal realm and the lived realities of colonial subjects.