Europe's Internet

Between fiber optics, regulated competition and privacy laws, most Americans might be surprised to learn the country that created the ARPANET, is not leading the world.

As Americans, we tend to assume that the invention of the internet was fundamentally an American achievement and that the strength of our tech sector means the homeland leads the world in technological innovation. The truth, however, isn't so straightforward.

The American internet is slow

Many factors affect internet speeds, including the distance data must travel to reach a given server, the number of "hops" a packet must make to reach its destination, and the allotted computing resources at each node in a connection. However, for many Americans, the bottleneck lies in the outdated infrastructure connecting them to the World Wide Web.

Just as road networks centralize long-distance traffic into highways, the internet centralizes traffic into cutting-edge fiber optic backbones capable of transmitting vast amounts of data in record time. But as any rural resident knows, a highway is only as good as the roads leading to it.

Today, most Americans connect to the internet over phone lines (DSL) or coaxial cable (commonly referred to as cable). While both technologies, under optimal conditions, can offer sufficient speeds to satisfy the average consumer, real-world conditions mean that millions of Americans suffer high latency and slow downloads just as everything in daily life has gone digital—including education.

Modern fiber optic technology, which transmits data by reflecting light, is significantly cheaper to lay than coaxial cable and can transmit much more data at much higher speeds over extraordinarily long distances. However, fiber has one problem that American ISPs seem reluctant to overcome: it requires investing in their infrastructure.

Not all fiber is equal. For example, when the European Commission talks about fiber, they refer to Fiber to the Premises (FTTP), meaning the fiber connection terminates inside the building it is intended to serve.

Stateside, ISPs marketing fiber are actually selling fiber-to-the-node or fiber-to-the-curb, meaning they are running fiber upstream from your house but not to your house. It feels a bit like when AT&T rebranded its 4G network as 5G.

The table below shows where the United States and Europe stand in terms of fiber deployment.

| United States | France | Romania | EU Avg. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households eligible for fiber | 45.6%* | 73.25% | 95.6% | 56.5%** |

*The US data refers to all types of fiber deployment, incorporating many FTTN or FTTC installations, which makes the US appear closer to the EU average than it is in reality.

**The EU average is greatly influenced by Germany, which, much like the US, has long pulled back from State-driven infrastructure investment.

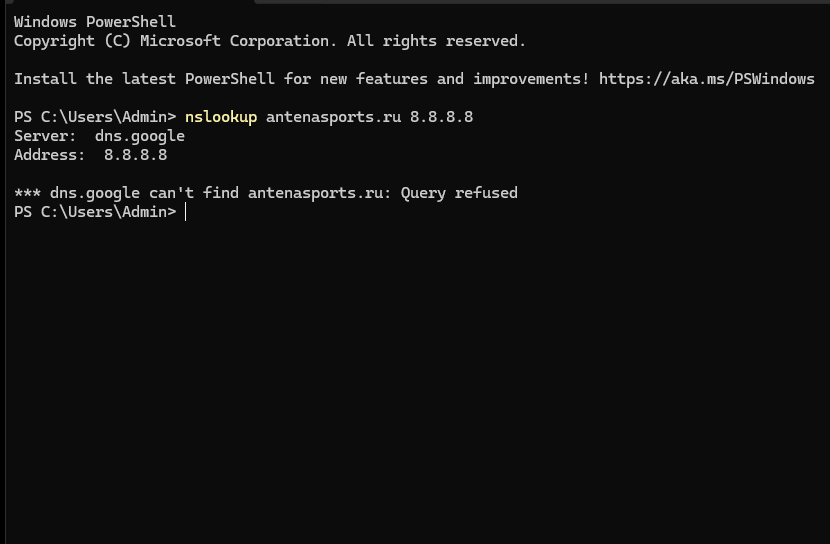

Methodologically speaking, proving that U.S. internet is functionally slower than that of most European countries is difficult, especially since indices like the Speedtest Global Index cannot paint an accurate picture of actual internet performance. This is due to the self-selecting nature of their user base, the inevitable reliance on their own infrastructure's ability to serve a fast enough connection to provide test results, and above all, the fact that most tests are likely performed on endpoint devices with NAT routers and weak Wi-Fi connections that slow things down.

And although ISP-advertised speeds cannot be taken for granted, they can still provide ballpark numbers to work with. Nevertheless, the comparison will inevitably be imperfect since, in the United States, ISPs may build their own infrastructure to different standards and offer a myriad of different speed and price offerings depending on location.

Americans pay way more for less

The following table compares the promised speeds and prices between select American and French operators.

| US: Veriozn FIOS | US: Xfinity | FR: Free | FR: SFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advertised Download Speed | 1.5 - 2.3 Gbps | 2 Gbps | 8 Gbps | 8 Gbps |

| Advertised Upload Speed | 1.5 Gbps | 200 Mbps | 8 Gbps | 8 Gbps |

| Price/month | 110 USD | 120 USD | 49 EUR | 45 EUR |

| Availability | Limited to select areas | Limited to select areas | General Availability | General Availability |

In France, Free offer 5 gigabit internet for only 29 euros per month.

Not only do the French pay significantly less for significantly higher-speed internet, but they also enjoy contract periods capped at one year and a highly competitive marketplace where they can easily switch operators—unlike in the United States, where only one or two ISPs may operate in a given area. Similar comparisons can be made with other European countries; for example, Bulgarians on the A1 network pay just 19 BGN (9.70 EUR) for gigabit internet!

Americans pay with their data too

If the U.S. Supreme Court found a right to privacy under the 14th Amendment, it doesn't seem to mean much in the digital age, where Americans find themselves subjected to constant online surveillance—whether on behalf of the State or private companies.

While no law can stop the NSA from tapping French President Emmanuel Macron's phone or stop Israeli surveillance companies from distributing spyware to malicious state actors, legal frameworks can clamp down on the gathering and sharing of sensitive data.

In Europe, national privacy regimes have long held stricter rules on data collection and processing. In France, this includes the so-called "right to private life," which is why, for example, people who are recorded (even in public) have their faces blurred out on European news channels. Moreover, the European Court of Justice has held that search engines like Google must respect the Right to Be Forgotten.

In 2016, European law took a strong stance on data collection and processing with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which remains the gold standard of data protection worldwide. Stateside, meanwhile, legislation akin to GDPR seems unobtainable—just as the EU is swiftly moving forward with a new directive aimed at regulating artificial intelligence.

In future articles, we will explore more ways in which the European internet differs from that of the United States—stay tuned!