French Court Orders DNS Providers to Block Queries to Illicit Sports Streaming Websites

On the basis of Article 333-10 of the Sports Code, DNS providers can be forced to refuse queries to websites streaming sports games. Is this censorship or run of the mill regulation?

In late September 2024, the Groupe Canal+ and the Société édition de Canal Plus, based on Article 333-10 of France's Sports Code, petitioned the Judicial Tribunal of Paris to order DNS providers Google, Cloudflare, Quad9, and Vercara to block access to websites allegedly streaming sporting events without authorization. The list of these domains can be found in Summons 1 and Summons 2. On the 5th of December 2024, the court ordered the defendants to block the referenced domains for users in French territory.

In a press release, the Quad9 foundation based in Switzerland used the phrase "DNS Censorship" to describe the legal challenge that this and other cases may pose to the foundation's mission of providing users with free DNS services featuring "robust security protections, high performance, and privacy." Quad9's General Manager John Todd, in an interview with Tom Lawrence, suggested that these types of legal actions are a slippery slope which could turn the internet into a "splinter-net" resembling the DNS censorship practiced in countries like China.

What is DNS?

Domain Name Service (DNS) is the internet's phonebook, correlating easy-to-remember domain names like google.com with the actual IP addresses where these websites can be reached. Since IP addresses often change while domain names usually remain constant, these services must be constantly updated and queried when a user wants to access a website. Fortunately, there are dozens of services that serve this function, from your local Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to the plaintiffs in the present case.

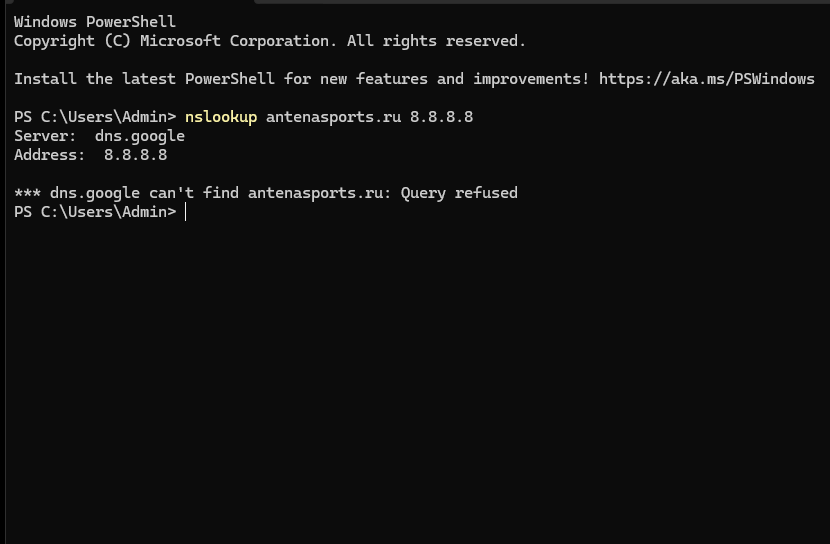

Readers following along at home can see this happen in real-time by opening Command Prompt on Windows or Terminal on MacOS and typing nslookup google.com. After a few milliseconds, the IP address corresponding to google.com should appear!

By default, most users will use their ISP's DNS service provider, which can be less than ideal for privacy and security reasons. It may also mean that you will be unable to resolve domains blacklisted by your ISP for legal reasons or otherwise. For these reasons and more, enterprises and advanced users typically opt to use an "alternative DNS" provider such as those offered by the defendants—preferably via DNS-over-HTTPS.

One of the benefits of using a robust DNS provider like Quad9 is that they use threat-intelligence monitoring to block malicious domains hosting malware or phishing operations. This means that when a user tries to access one of these websites, the request fails because the DNS provider refuses to answer the query. If you have young kids at home, you can also use one of the family versions of Cloudflare or Quad9's DNS services to block access to adult content.

DNS Censorship?

Since all defendants in this case exercise some degree of self-censorship—whether for stopping malware, thwarting phishing, or protecting children from pornography—it may seem like a stretch to demand these providers ban content according to France's copyright law. This can be traced back to an ideological fetishization of technology that views computation not as a project embroiled in American militarism and empire but as a force of nature destined for liberation. In this distorted view, legitimate regulation is decried as censorship; hate speech is reborn as free speech, and nation-state borders are reduced to fictions which technology should obliterate.

In this outlook, it seems perfectly legitimate for a democratic nation like France to prohibit illicit film projections in theaters or subject hate speech to criminal sanction. However, applying these rules in cyberspace would be seen as Stalinism. This ideological inconsistency is grounded in the fact that many proponents wield it cynically to protect Silicon Valley from regulation or promote American hegemony. For more on this topic, see Yasha Levine's All EFF’d Up and his reporting on the Tor Project.

The so-called censorship is more akin to run-of-the-mill regulation that has always limited speech, regulated telecommunications, and held back free-market excesses. It's this type of regulation that should be opposed—not because it impacts an abstract notion of free speech but because it may not make sense for a powerful company like the Canal+ Group, controlled by the Bolloré family, to act as gatekeepers of popular pastimes and national sports (see our article on French Media).

Intellectual Property in the AI Age

Copyright law was universally opposed by 1990s techno-libertarians who saw it as an impediment to the free flow of ideas and a tool for preserving the extortionary capacity of music labels and film studios, which could pay their creative labor little while charging consumers monopolistic prices. This analysis, if essentially correct, would fail to explain how AI companies and their LLMs can be built and distributed in blatant defiance of positive law.

This is because copyright law is not merely a creation of positive law but rather the property relationship that copyright holders seek to assert over their commodities. This situation is analogous to that of a landlord and a squatter in an unused building—the latter costs the landlord nothing, yet must be evicted to preserve the social fact of a landlord's dominion over property.

From this perspective, we can question the soundness of the plaintiff's argument that these illicit streaming websites cause them harm. This argument is recurrent in anti-piracy discourse and often draws a false equivalency between stealing a physical DVD and stealing a digital file—the former is an actual loss, while the latter costs the rightsholder nothing. The only theoretical harm is the difference between what the rightsholder made and what they could have made, which does not operate at a 1:1 ratio. Much like the squatter, the pirate may lack the money or desire to pay the extraordinary prices rightsholders demand for streaming a football match, while others might just go to a friend's house. Moreover, illicit consumption patterns differ from paying ones. Consider someone who pirates 100 movies in a year: do we really believe that if it weren't for illicit downloads, this person would have purchased 100 Blu-ray discs or signed up for a dozen different streaming services? What about Library Genesis—do we really think underpaid academics would spend thousands of dollars per month just to read a few academic papers?

This is supported by the very report from ARCOM cited in the plaintiffs' case against DNS providers, which shows that the main reason respondents resorted to illicit streaming was due to high prices offered by licit services (see p. 112 of the Baromètre de la consommation des contenus culturels et sportifs dématérialisés - édition 2023). Furthermore, the report demonstrates that illicit sports streaming is marginal and licit consumption is on the rise. Where illicit consumption remains strong is among the young and unemployed—i.e., those who probably wouldn't become customers if the illegal option weren't available.

If there's a reason to be outraged, it isn't because this is the first step toward Stalinist censorship but because democratic institutions are being wasted trying to block access to domains like antenasports.ru and their dozens of counterparts. These can all be accessed by simply turning on a commercial VPN, using a DNS server that ignores French law, or starting a local recursive DNS server with software like PiHole.